In defense of not reading the code

Last week, I wrote an article whose purpose was to discuss where I saw AI-assisted coding going. That's not what generated 200 comments worth of passionate...

Last week, I wrote an article whose purpose was to discuss where I saw AI-assisted coding going. That’s not what generated 200 comments worth of passionate debate. The line that got the discussion going was, “I don’t read the code anymore.”

I can’t imagine any other example where people voluntarily move for a black box approach. Imagine taking a picture on autoshot mode and refusing to look at it. (kace91)

I thought a lot about these arguments, and I still don’t read the code. I think it’s worth clarifying - by ‘I don’t read code,’ I mean: I don’t do line-by-line review as my primary verification method for most product code. I do read specs, tests, diffs selectively, and production signals - and I would advocate escalating to code-reading for specific classes of risk.

I think more people should stop reading the code not because the code doesn’t matter, but because reading it is increasingly the wrong way to ensure it’s right, especially at scale.

The evidence is piling up

OpenAI Harness Engineering

Here’s some evidence to show that I’m not the only one that thinks this way. In a very timely post, OpenAI today wrote a blog post where they talked about what they called “Harness Engineering”.

We needed to understand what changes when a software engineering team’s primary job is no longer to write code, but to design environments, specify intent, and build feedback loops that allow Codex agents to do reliable work.

It’s about how they built an entirely new product where every line of code was written by Codex agents. No human-written code at all. They had three engineers, they produced a million lines of code, the product is used by hundreds of internal users, and what they invested in was not code quality, it was the harness around it: docs, dependency rules, linters, test infrastructure, observability. What they didn’t invest in? Reading the code line by line.

OpenClaw

A second example that anyone online has heard a lot about is OpenClaw, which was created by one person with no team. It’s one of the fastest-growing open source projects in recent months. He built a personal AI assistant that has 100,000+ GitHub stars. He runs 5-10 agents in parallel. This is not a novice; he is an experienced engineer.

I ship code I don’t read

He recently did an interview that was entitled “The Creator of OpenClaw: I ship code, I don’t read.” Similar to me, similar to the Codex folks, he invests heavily in refactoring, architecture, testing, and the harnessing that lives around AI coding.

From Coder to Orchestrator

My final example is this recent article - a career software engineer who created ESLint and has written multiple O’Reilly books about coding, who recently wrote an article whose argument is basically: software engineering in the future will not involve writing code; it will involve orchestrating AI agents. He says that the skills that matter are shifting from syntax and implementation to architecture, specification, and feedback loop design.

The skeptics

I think those are some pretty strong arguments, but there were some specific arguments in the discussion, so I’m going to address a few of them.

Black box

I can’t imagine any other example where people voluntarily move for a black box approach (kace91)

The first critique is - it’s a black box. A commenter put this well - The output of code isn’t just the code itself, it’s the product. The code is a means to an end. So the proper analogy isn’t the photographer not looking at the photos, it’s the photographer not looking at what’s going on under the hood to produce the photos. Which, of course, is perfectly common and normal. Building on layers of abstraction that we don’t look at is already a common practice in many engineering processes, including software engineering.

Security

You made me imagine AI companies maliciously injecting backdoors in generated code no one reads, and now I’m scared. (thefz)

I take this seriously. But I think this is a tooling problem, not a “read every line” problem. Static analysis, dependency scanning, and security linters exist precisely because humans also write insecure code. The answer is better automated verification - which is exactly what the harness-first approach emphasizes. For genuinely security-sensitive surfaces, yes, human review still matters. I’ll come back to that.

Bugs will compound.

If my code fails people lose money, planes halt, cars break down. Read. The. Code. (frank00001)

I think that was the most common critique, which I think is fair. From CodeRabbit - AI-generated code introduces 1.7x more defects across every major category of software quality.

My response - there are many different forms of AI coding right now. Developers who are operating in a harness-first way with specs and layered testing and architectural constraints are a lot different than people who are just vibing and typing. I found this comment to match my intuition & approach:

I mostly ignore code, I lean on specs + tests + static analysis. I spot check tests depending on how likely I think it is for the agent to have messed up or misinterpreted my instructions. I push very high test coverage on all my projects (85%+), and part of the way I build is “testing ladders” where I have the agent create progressively bigger integration tests, until I hit e2e/manual validation. There’s definitely a class of bugs that are a lot more common, where the code deviates from the intent in some subtle way, while still being functional. I deal with this using benchmarking and heavy dogfooding, both of these really expose errors/rough edges well. (CuriouslyC)

I think the question we ultimately need to answer is not “Does AI code have more bugs on average?”, it’s, “Does AI code within a well-designed harness produce more bugs than the alternative at the same velocity?” Building on that - and I’ll come back to this - which approach is going to improve more quickly? I think that’s the fair bar. It’s not, “Is this perfect?”, it’s, “How does it compare to the alternative?” Greg Brockman, OpenAI’s co-founder, tweeted about this recently - he expressed a common sentiment I share - “maintain the same bar you would have for human-written code.”

What this looks like (my system)

I think this is probably a good time to talk about my own system. I’ve written code for most of my career, mostly internal tools, but they are real things that real people depend on and use. I know how code looks. I know what it should look like. I’m choosing not to look at it. Here’s what I do.

My previous posts talked about this, but before agents write code, I write specs - very detailed specs facilitated by AI conversations. They’re heavily structured with requirement IDs that trace from the product spec through to the execution plan. Every task in the execution plan has acceptance criteria tagged with how they’ll be verified: (TEST) for automated tests, (BROWSER:DOM) for visual checks, (MANUAL) only when nothing else works - and even then, the system tries to auto-generate a curl or bash check before falling back to human eyes. If a task doesn’t have concrete verification metadata, an audit skill catches it before work begins.

I think it’s important to talk about this because when people hear, “I don’t read the code,” I think they believe I don’t take the code seriously. I do. I just focus on the spec layer and the harness and the architecture. That’s where my attention goes, and the code is an output of that process, not the thing I manage directly.

My Harness (AI Coding Toolkit)

My harness is a toolkit of prompts, skills, hooks, and scripts that constrains how agents work. It’s not a single file - it’s 35+ skills, structured agent instructions, and layered verification infrastructure. Here’s what it actually enforces:

Agent instructions as infrastructure. An AGENTS.md file acts as the primary rulebook: conservative edits, don’t break existing interfaces, TDD, don’t speculate - ask. Don’t rewrite git history. A VISION.md defines strategic boundaries.

Layered verification, not line-by-line review. After each phase, a checkpoint skill runs a multi-layer gate: type checking, linting, tests, build, mutation tests, security scan. If browser tools are available, it runs automated browser checks. Then (one of my favorite pieces) it sends the diffs to a different AI model (Codex CLI) for a second-opinion review. Cross-model verification catches the things that a single model’s blind spots would miss.

Most of my code is generated using this toolkit - detailed, structured specs with stringent testing and acceptance criteria, and then executed using a harness that constantly checks itself.

I do think it’s worth saying I do sometimes read the code. It’s just the exception to the rule. When everything’s passing but the product feels wrong… or I’m making a big architecture decision… or I’m debugging a failure that multiple agents haven’t been able to resolve, I will in those cases look at the code. But even when I do, I am generally trying to figure out what the gap in the harness is so that I don’t have to address this problem again.

When to read the code

That leads me to the section on caveats that my original article didn’t cover primarily because that wasn’t the point of the article, but those caveats are:

There are cases in which you need to read the code. Safety-critical systems, security-sensitive services, significant architectural decisions, software engineering is engineering in those cases. It matters enormously, perhaps more than ever, because of how much code is being generated now.

There’s an analogy from aviation that I think is useful here and it’s called “Children of the Magenta.” The name came from pilots who were dependent on following the magenta line, which is the programmed flight path that was displayed in magenta on navigation screens. I encourage you to read the linked article, which was really interesting.

From the article:

Vanderburgh understood earlier than most that automation dependency wasn’t just about the technology itself, but about losing the judgment to know when to use it. Crews were becoming task-saturated trying to maintain the highest level of automation in situations that called for dropping down to basics.

The lesson in that case wasn’t “don’t use autopilot”. Autopilot is great, and a huge reason that planes are so safe today. The lesson is you use it but you need the ability to intervene. When something goes wrong, you step down the level of automation. Even so - you wouldn’t ask pilots to fly every flight manually; that would be less efficient and more dangerous. That’s the kind of balance I think I’m getting at here.

Bet on the trajectory

Every layer of abstraction in computing has met resistance. Cline has a great post about it: From Assembly to AI: Why ‘Vibe Coding’ Is Just Another Chapter in Our Abstraction Story - Cline Blog

But perhaps the most relevant historical parallel to today’s “vibe coding” debate happened in 1973. Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson decided to rewrite Unix in a new language called C. The idea of writing an entire operating system in a high-level language was considered absurd.

Critics argued:

- It would be too slow

- You’d lose control over the hardware

- The added complexity would make the system unmaintainable

Instead, C’s abstraction of machine details enabled Unix to become one of the most portable and influential operating systems ever created. Like Ritchie said - “Unix is very simple, it just needs a genius to understand its simplicity.”

The pattern remains: People whose expertise is in the layer that is being abstracted argue that you need to understand that layer, and they are right. Some people do, and in some cases, but most people’s time and most time is better spent at the higher layer of abstraction.

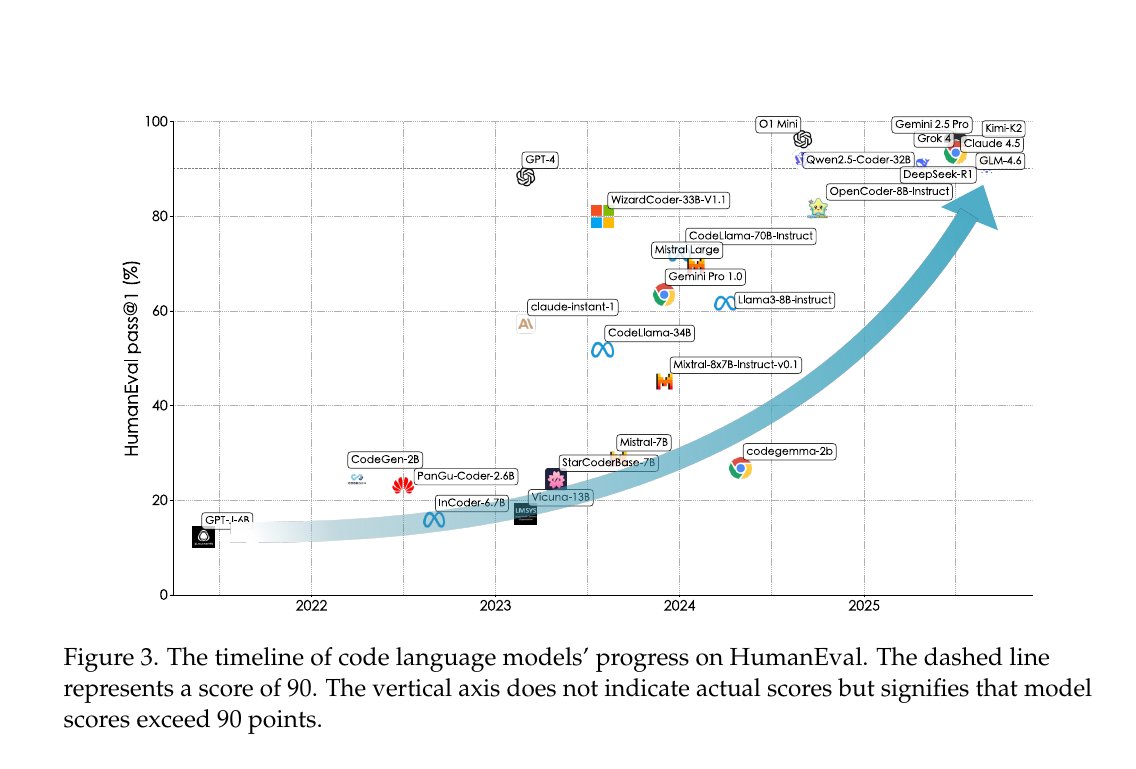

Not reading the code is a bet on the trajectory. It’s not saying that the tools are perfect; it is saying that the tools are good enough for many use cases, and that they are improving incredibly quickly. If you’re betting, I think you bet on the side of the models continuing to improve.

I’m not asking people to be reckless. People should update their priors. Code is often becoming an implementation detail; the spec, architecture, and verification layer are becoming the artifacts that matter. I don’t think the code doesn’t matter; I just think that reading it and interacting with it directly is not how you make sure it is correct.